Given the pace of news these days, you may already have forgotten the story of the illegal Ethiopian immigrant. A week after landing on the Kent coast, the man tried to kiss a fourteen-year-old girl. She was minding her own business on a park bench, eating pizza with a friend; up stepped the illegal immigrant, one of 39,294 small boat arrivals to the United Kingdom to date in 2025 – and the year isn’t over yet.

When the girl protested her age, the man told her age that ‘did not matter’. He said he wanted to have a baby with her and another one with her friend. He touched the girl’s thigh; for good measure, he also touched up an adult woman who tried to intervene.

In court, he insisted that he was not an animal. Maybe, but he is clearly a man who thinks he has the right to touch any girl or woman without her consent. That’s evidently what men get away with in Ethiopia. To my knowledge, he has never expressed remorse; he was sorry only that his actions caused protests against his fellow-illegal immigrants.

Political liberals may be annoyed by the term illegal immigrants. Democracy is a fine thing, but if we can’t label objects and persons by their proper nouns, we’ll never get to the heart of any issue. And if we can’t get to the heart of this issue, we don’t have a hope in hell of solving it.

Incredibly, there are people in Britain who don’t even think we have an immigration problem. They must be living on another planet (or the Shetlands). As our brave Home Secretary, Shabana Mahmood, said when introducing her immigration reforms on 17 November 2025:

‘This country will always offer sanctuary to those fleeing danger. But we must also acknowledge that the world has changed, and our asylum system has not changed.’

Exactly. The UN conventions governing refugees were drawn up in 1951. 1951, imagine! Can you seriously expect a charter established when the world was such a different place to still be fit for purpose in 2025?

Actually, we don’t need to go back that far. England has changed dramatically since I arrived for school 46 years ago in 1979. When I landed at Heathrow Airport, Margaret Thatcher had only just been elected and Britain, having endured a Winter of Discontent, was still reeling from the ignominy of being bailed out (in 1976) by the International Monetary Fund.

Life then was sedate and quintessentially British. Tea remained the drink of choice; shops closed at 5 pm and telephones were coin-operated. There were rules. People expected these to be respected. To someone from a former British colony, things looked different yet also vaguely familiar.

The Malaysian education system which produced me was based on the old British system and I settled in easily enough. I stayed on, first as a university undergraduate and then as a research student on a Physics Ph.D. programme. For my entire first decade in the United Kingdom, I was here on a student visa, which meant I could not work.

In that era, it was a badge of honour for British Ph.D. students, especially those in the humanities, to dawdle over their theses. People commonly took 5, 8 or even more than 10 years writing up. I did not have that luxury: as a foreign student, I was not eligible for a student grant and I’d had to win special funding for my Ph.D. degree. The funding – from Southampton University – lasted 3 years, not a day longer. As my third postgraduate year kicked in, I knew I would have to write up my thesis and look for a job at the same time.

There was no Internet back then. To research career options, I headed to the University’s Careers Service, where I spoke to the Careers Officer. He made many helpful suggestions. I followed them all up, spending hours carefully parsing through corporate brochures, then honing my slim CV and crafting cover letters. Students in my time were expected to know how to write formal letters. Interviews, when you got one, were face-to-face.

I applied to dozens of firms. All of them turned me down without even an interview. They told me that the Home Office would never grant a work permit to an entry-level employee. My Ph.D. (in Theoretical Physics) didn’t mean a thing if the work could be done by a native or a European.

My only hope was an academic job. Meanwhile the clock was ticking; if I didn’t get a move-on, time would run out on my student visa. I had to pull my research results together and write them up into a coherent whole. And I had to do this not knowing which country I would end up in or how I was going to earn a living.

Malaysia was my Plan B. As a Malaysian passport holder, I could (and can) always return there. There were only three problems: I have the wrong ethnicity (Malaysian-Chinese), the wrong religion (non-Muslim) and the wrong sexual orientation (considered haram). Even today, homosexuality is illegal in Malaysia. For someone who has tasted freedom, life in the closet is hard to contemplate.

At almost the last minute, a research fellowship at St Catherine’s College, Oxford, came up. Oxbridge fellowships are prestigious and highly competitive. But I had no connection to the University and was surprised to be shortlisted for an interview. When I walked into St Catherine’s for the very first time, it felt somewhat intimidating. I was grilled by a panel of five. You can feel when an interview is going well – and I sensed it going very well. The College offered me the job at once. What they wanted me to do was so arcane that I doubt if anyone in the Home Office understood my full job description. In those days the British government actually controlled immigration.

That’s no longer the case. Now, alongside a legal but woefully lax official system of immigration is a black market on Tik Tok. Small boats are big business. Just look at the advertisement below.

The image comes from Global Initiative, but you can find plenty of others. Facebook, Snapchat and Instagram are all crime-enablers; the rage, however, is apparently Tik Tok. Small boat ads are so well-documented, even the BBC has mentioned them.

People-smugglers know their target audience. They price their offerings appropriately and deploy creative tactics: for instance, giving price discounts to customers who help with social media marketing. Small boat customers, like customers of legal services, shop around before choosing their preferred country and preferred smuggler.

This is what the Home Secretary meant when she said:

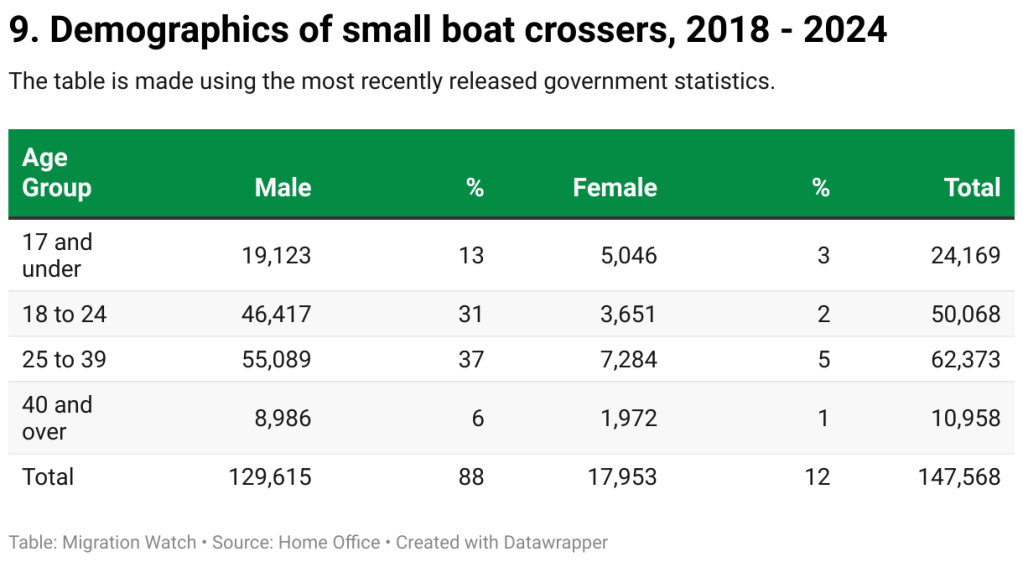

88% of arrivals on rubber dinghies are male (see data below, taken from Migration Watch UK, Source: the Home Office). And yet, in most parts of the world, it’s women who are more likely to face persecution simply because we have XX chromosomes; historically, groups genuinely fleeing danger have been evenly split by gender. No matter how you view the world, the extreme gender skew of small boat arrivals should be a red flag.

The mix of source countries changes from year to year; in 2024 the men came mainly from Afghanistan, Syria, Iran, Vietnam, Eritrea, Sudan and Iraq (source: Migration Watch UK). Granted, these countries are all poor, but can you really call someone who has chosen to leave poverty and a Communist regime (Vietnam) or poverty and the rule of mullahs (Iran) a refugee?

And if they really are in the grave danger they claim to be in, why not just stop in the first safe country; why cross so many more borders and crown their risk by jumping into a rubber boat?

As Shabana Mahmood said:

‘… even genuine refugees are passing through other safe countries searching for the most attractive place to seek refuge.’

When Hitler was gassing Jews in Germany, the few Jews who managed to escape were relieved to be somewhere safe; they did not shop around on apps looking for ‘better’ countries. If you’re already in a safe country, be that Italy, France or Belgium, and you keep crossing borders and then climb into a dinghy, that act of deliberately putting yourself in more danger (and in some cases, your children, too) should surely disqualify you from gaining asylum in Britain.

Some will argue that only desperate people would put themselves in deliberate danger; therefore, they deserve our empathy and compassion. My counter-argument is that there are now plenty of legal immigration routes into Britain (many more than in my day), but if you know you would not qualify legally, you look for illegal means.

In other words, small boat customers know very well that they’re breaking laws. If someone knowingly breaks the law before they even get to Britain, why should we expect them to obey our laws once they’re here? The simple answer is: we can’t.

Denmark was the first European country to collect data about its immigrant population. What the Danes have found is that foreigners are over-represented in Danish criminal convictions relative to their population size.

Put simply, if 15 out of every 100 people in the population are immigrants, then, all things being equal, you would naively expect 15 out of every 100 criminals convicted to be immigrants. In 2023, 15 out of every 100 people in Denmark were immigrants. But immigrants made up 25 out of every 100 people convicted of crimes.

The same over-representation of foreigners in Danish criminal convictions was found in 2022, 2021 and every single year for which the data was available – going all the way back to 2014, when data was first collected.

I can already hear objections. ‘This simply means that Denmark is a racist country. You’re more likely to be convicted of crime if you’re a foreigner!’

Not so fast. Danish data also suggests that not all immigrants are equal. Immigrants to Denmark from the Philippines, Indonesia, China, India and Argentina are less likely than locals to be convicted of crime. Bottom of the criminal list is Japan: the Japanese in Denmark are incredibly law-abiding. To sum up, not all immigrants to Denmark cause problems: only those from the Middle East and North Africa. Alas for Britain, these have been our main source countries in recent years.

Until liberals are prepared to concede that there just might be bad immigrants, debate around immigration will remain toxic. Pro-immigration Brits behave as if they stand on hallowed ground. They claim to be against ‘racism and fascism’; by implication, if you dare question immigration, you must be racist, fascist, ignorant and evil.

The slogans haven’t changed since I was at university 40 years ago. Slogans have always been cheap; in the age of instant social media, they are especially cheap. Where was the anti-racist, anti-fascist brigade when a Jewish economics lecturer in London was hounded inside his lecture hall? Professor Ben-Gad, himself an immigrant – but a highly-educated immigrant, not the sort usually favoured by the great and the good of the left – was threatened with beheading by masked pro-Gaza supporters. This happened in central London, not some godforsaken ISIS territory; if we don’t want beheadings and hand-chopping to become acceptable in Britain, we need honest dialogue in this country.

Not all immigrants are equal. Not all immigrants are good. And not all immigrants want to integrate.

For the record, I’m not against immigration, but I am absolutely 110% against uncontrolled, unfettered immigration. I played by the rules. The immigrants I know – and I know plenty – have also played by the rules, jumping through hoops (not into rubber boats) to ensure that we obeyed the laws of this country. Some of the rules themselves have become tougher for legal immigrants, thanks to their widespread abuse by people who don’t care about rules. How is it fair on those of us who have obeyed every law, to watch people clearly exploiting loopholes and be allowed to exploit them? Those who turn up in Kent when their countries are clearly not at war; those whose asylum applications are rejected but who stay anyway, supported by our taxes, often for years, while they appeal and re-appeal: how is any of this fair?

To quote Mahmood once again:

‘…we have a proper problem and it is our moral duty to fix it. Our asylum system is broken. The breaking of that asylum system is causing huge division across our whole country, and it is a moral mission for me to resolve that division across our country.’

Her reforms are a start. Personally, I don’t think they go far enough. She hasn’t even begun to tackle the problems in our legal immigration system. But Shabana Mahmood is to be lauded because no one else has had the balls to do even as much as she has.

I, an immigrant, support her efforts. I don’t want illegal men here. And I know I’m not the only one.